SLS Hale Lecture: The Future of Law Reform

Read the speech the Chair of the Law Commission, Sir Peter Fraser, gave for the Society of Legal Scholars SLS Hale Lecture 2024

(1) Introduction

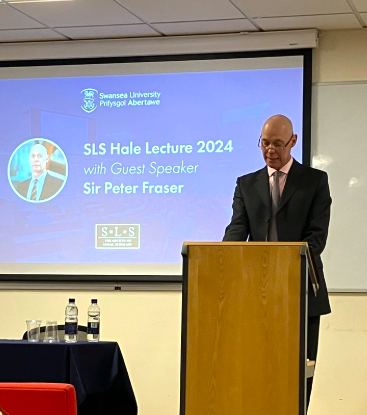

The Chair of the Law Commission, Sir Peter Fraser, delivered the SLS Hale Lecture 2024 last week, which was organised by the Society of Legal Scholars and hosted by Swansea University’s School of Law.

The lecture was entitled ”The Future of Law Reform”.

The full speech can be be viewed on this link, or viewed below.

- It is a pleasure to have been asked to give the SLS Hale Lecture. It is rather humbling to have so many of you give up your time to come and listen to me; it is particularly humbling for me to be delivering this lecture in the presence of so many distinguished lawyers, but particularly Baroness Hale herself, who spent an early part of her career at the Law Commission and who is a great friend to the Commission. My focus, you will not be surprised to hear, is the future of law reform. 2025 is, after all, the sixtieth anniversary of the creation of the Law Commission of England and Wales. However, we can all learn from history – there are some who say that history endlessly repeats itself – and so this lecture will also deal with some history too.

- Law reform did not of course begin in the 1960s. When Lord Gardiner introduced the Act to the House of Lords, he said the following, and gave a powerful example of why the Commission was needed. [Quote]

- As Lord Scarman, the first Chair of the Law Commission noted in 1973,

‘It’s rather common to think that law reform began in 1965 when the Law Commissions Act was passed at the insistence of Lord Gardiner, the Lord Chancellor of the day. This of course is quite untrue. Law reform has been part and parcel of the common law world, certainly ever since Henry II.’

He then went on to note how our common law courts had been subject to reform during the 19th century, having lasted since the time of the erstwhile Henry II. How reform had been the order of the day during and after Cromwell’s time. He might also have pointed out how the 19th century saw law reform with more than 60 reform Commissions appointed, a significant number of which looked into how to improve our courts and judiciary. And that was only the tip of the iceberg. That century also saw significant consolidation of the statute book, reforms of weights and measures, of the law of bankruptcy, shipping law and so on. - Things were a little quieter during the first half of the 20th century, although with the creation of the Law Revision Committee in 1934, and then the Lord Chancellor’s Law Reform Committee in 1952, things moved a little quicker again. And then came Gerald, Lord Gardiner and 1965. He had been a committed reformer since his university days, and was undoubtedly a great man very considerably ahead of his time. He was threatened with suspension from his university studies for his law degree for publishing in 1922 ‘a pamphlet attacking restrictions on women undergraduates.’ His focus on the reform of law reform can, however, probably be traced back to 1947. In that year he was appointed to the Evershed Committee, which was responsible for examining and making proposals to reform the practice and procedure of the High Court. It deliberated until 1953 and produced three reports. On one view its work could be described as painstaking. Another way of looking at it, and the one Lord Gardiner took was that such an approach was indicative of a need ‘more effective’ mechanisms to be established to effect law reform. He was not alone. Lord Reid, one of the great Law Lords of the 20th century, made this telling point when speaking in the House of Lords in the debates during the creation of the Commission, ‘. . . you cannot expect good results from an ad hoc committee which has no adequate staff, which meets only occasionally in the evenings, and members of which cannot attend every meeting. It really will not do at this time of day to remit complicated issues to bodies of that kind.’

- Once appointed as Lord Chancellor in 1963, Gardiner was able to put into action his desire for a more systematic approach to law reform. No longer was it to be left to ad hoc committees. No longer was its focus to depend upon the particular interests of individual Parliamentarians. No longer was it to be carried out to an uncertain timescale where ‘recurrent phases of stagnation’ would follow on from periods of frenetic activity. On the contrary, law reform was to be considered, comprehensive, and carried out by a permanent reform body guided by a clear purpose, and specifically established to do that. The body, or rather bodies, were to be the Law Commission for England and Wales and the Law Commission for Scotland. Their purpose was, as made clear by section 3 of the Law Commissions Act 1965, ‘. . . to take and keep under review all the law with which they are respectively concerned with a view to its systematic development and reform, including in particular the codification of such law, the elimination of anomalies, the repeal of obsolete and unnecessary enactments, the reduction of the number of separate enactments and generally the simplification and modernisation of the law . . .’

- It was suggested by some at the time of its creation that this ambitious aim was unlikely to be realised. Parliament, it was suggested, would be unlikely to take up the Commission’s reform proposals. The Commission would, in essence, be a worthy waste of time. The cynics’ expectations have, of course, been utterly confounded. From 1965 to 2024, the Commission published 256 law reform reports. 63% of those reports have been implemented in whole or in part, with a further 8% having been accepted with implementation expected. Only 12% have been rejected, while 4% have been superseded by other events. Very recently, we have had the Insurance Act 2015; the Leasehold Reform Act 2024; the Arbitration Bill 2024-2025 is going through Parliament at the moment, as is the Digital Assets (Property) Bill 2024 too. The Electronic Trade Documents Act 2023 was passed recently, based entirely on a Law Commission report recommending such a reform.

- No organisation should, however, rest on its laurels. Complacency and basking in the reflected glow of your greatest hits – or in my case, given I became Chair just over a year ago, the greatest hits of the band before you became a member – is certainly not something that a reform commission should engage in. If the Commission is to continue to realise its purpose there is, I believe, a need for it to be guided by six principles or themes. There is also a need for one significant structural reform to its constitution. It is to those that I now turn.

(2) Structural Reform – A Fifth Commissioner

- First, the structural reform. The Law Commissions Act created two Commissions, one for England and Wales and one for Scotland. Northern Ireland would not have an equivalent to the Law Commission until 1989, when its Law Reform Advisory Committee was established. It was replaced in 2002 by the Law Commission of Northern Ireland, albeit it is currently non-operational. The reason for two Commissions under the 1965 Act was straightforward. England and Wales formed a single legal jurisdiction, which was separate from that of Scotland. Just as the two had separate legal professions, courts and judges, they had separate laws. It thus made eminent sense to have one Law Commission for each jurisdiction, with the Law Commission of England and Wales in limited circumstances also looking at the laws of Northern Ireland. Much has changed in society since 1965 – you have already heard from Lord Gardiner about the number of High Court judges there were in 1965 – about 60. Now, there are 108. There were four Law Commissioners for England and Wales in 1965 – now, 60 years later, there are still only four. The number of Commissioners has failed to keep pace with the increase in the population, the complexity of the law, the fast moving changes in society.

- Also, since 1965 much has happened to the constitutional relationship between the nations that make up the United Kingdom. The late 1990s and early 21st century brought and then developed devolution. The Government of Wales Act 1998 created the Welsh Assembly, the Senedd. Its successor the Government of Wales Act 2006 took devolution further, as have the Wales Act 2017. Devolved institutions, particularly executive and legislative ones, provided the clear basis for divergence between the laws of England and those of Wales. Tribunals in Wales are entirely separate and are under the President of Welsh Tribunals, Sir Gary Hickinbotham, a former Court of Appeal Lord Justice. This divergence has seen the Law Commission engage in detailed study of the Laws of Wales.

- For instance, from 2003 to 2013, the Commission examined the law as it concerned residential housing, specifically renting residential properties, in Wales. Those reports ultimately resulted in the Renting Homes (Wales) Act 2016. In turn that led to changes to the operation of the courts of England and Wales. Divergence in substantive law leading then, for the first, time a divergence in the procedural law of the two jurisdictions, with separate provision being made in the Civil Procedure Rules for claims between landlord and tenants depending on whether the claim relates to property in England or in Wales. Individual reform proposals have been matched by a broader approach by the Commission. In 2016, for instance, the Commission published a detailed report on the Form and Accessibility of the Law Applicable in Wales; a project that had been proposed to it by both the Welsh Government and the Commission’s own Welsh Advisory Committee. Unsurprisingly, the Report recommended, amongst other things, that a policy of codification twinned with reform of the laws that were within the competence of the Welsh legislature.

- The divergence in the Civil Procedure Rules, and the likelihood that it would increase as time went on, led to the revision of the membership of the Civil Procedure Rule Committee, the body responsible for those Rules. It also led to the revision of the membership of the Civil Justice Council, which complements the Rule Committee, by keeping the civil justice system of England and Wales under scrutiny. In 2017 the constitution of the Rule Committee was amended by statutory instrument to require that one member of the Committee must be a judge with particular experience of the law as it is applicable to Wales. As the then Master of the Rolls, Lord Etherton, put it, ‘Given the impact of Welsh legislation on the CPR, such expertise is as essential as it is beneficial.’ In 2019, the Civil Justice Council followed suit, reformed its membership and since that time has also had a member who also has particular experience of the law as it is applicable to Wales. Again as the then Master of the Rolls put it, a Council member with such experience would ensure that the Council’s proposals, and ‘particularly its modernisation proposals, are appropriate for the developing needs of local justice in Wales.’

- Since its creation the Law Commission has a Chair and four Commissioners, as required by section 1(1) of the 1965 Act. One of those Commissioners is, of course, well known to this lecture series. From 1984 to 1993 a certain Brenda Hoggatt, as she then was, served as a Commissioner. We now know her as Lady Hale and we are all delighted to see her here this evening. Each Commissioner is highly distinguished in their field. They have historically had defined areas of responsibility: criminal law; public law; property, family and trust law; and, common and commercial law. Professor Alison Young is currently the Law Commissioner for Public Law. She is also responsible for law in Wales. The law in Wales, of course, is not limited to public law; a point that is readily apparent if we recall the Commission’s three reports on residential property. Indeed, as the Commission concluded nearly ten years ago now, ‘it has become meaningful to speak of Welsh law as a living system for the first time since the Act of Union in the mid sixteenth century’. Whether the solution is a dedicated Commissioner for the law in Wales, just as it called for a dedicated member with specific knowledge of the law of Wales of the Civil Procedure Rule Committee and the Civil Justice Council, both of which have a more focused remit than the Law Commission, or whether the solution is simply another Commissioner, to enable us to improve the resource and organisation of the Commission, does not for these purposes much matter in my view. The important thing is that we have another one.

- The elimination of anomalies is one of our purposes, as is the modernisation and simplification of the law. Reform of the law. The creation of a new, a fifth, Commissioner whether or not one with specific responsibility for the law of Wales is in keeping with each of these objectives of the Law Commission. The appointment of an individual as a Commissioner with specific knowledge and experience of the law of Wales would be a significant step forward for the Commission; one that might be thought to be long overdue given the length of time devolution has been in place and given the growth of Welsh legislation. I very much hope that we see this reform come to pass before too long. It is, in my view, a reform that will help ensure that the Commission is more than fit for the future; for one where legal plurality across the two legal jurisdictions for which it is responsible will increasingly be the order of the day.

(3) Economic Growth and the Rule of law Domestically and Internationally

- Having considered structural reform I should now turn to the six principles or themes that I believe should guide the Commission.

- It is well-recognised that economic growth rests on the extent to which a country gives effect to the rule of law, and equally the extent to which the rule of law is observed internationally. It is a point that has been stressed in recent years both the last three Lord and Lady Chief Justices as well as the current Attorney-General. As Lord Burnett CJ put it, ‘The enduring lesson is that good governance and the rule of law enhance prosperity and well-being.’ A commitment to the rule of law has several elements: ready access to lawyers to obtain high quality legal advice so that individuals and businesses can understand their rights and obligations, and can properly order their affairs, enter into contracts, transfer property and so on; effective access to courts to resolve disputes via judgment as well as effective access to other forms of dispute resolution process; access to court judgments as a means to guide both of the former. Underpinning all of these factors is a framework of legislation, which is itself clearly stated and hence readily intelligible, readily accessible, and generally applicable. It ought to be unsurprisingly that Lord Bingham identified these features as essential general principles underpinning the rule of law. The rule of law also provides certainty – people and companies know where they stand, what is likely to be the outcome in any particular situation, and also promotes and demonstrates fairness and justice.

- Two recent examples illustrate how the Law Commission has and is contributing to maintaining legislative intelligibility and accessibility, and through that playing a role in the maintenance of our framework for economic growth. The first is our project reviewing the law concerning co-operatives. We were commissioned to look at this area by HM Treasury. Co-operatives are very dear to my heart. We moved house around the UK a great deal as children and spent a large part of childhood in the North of England. There, co-operatives are part of the structural fabric of society; their origin is groups of people, often of lower economic means, grouping together to help each other and share the economic benefits of trade. There are significant potential economic benefits from reform in the area of co-operatives. As our consultation paper put it,

‘Co-operatives are associations of consumers, producers, workers, or a mixture (called multi-stakeholder). Part of their purpose is to harness economies of scale. For example, when producers or workers combine as members of a co-operative, the co-operative might command better prices in the market for the produce or labour. When consumers combine as members of a co-operative, the co-operative might access cheaper prices for goods or services. The co-operative can then pass on those better prices when selling to its consumers, buying from its producers, or paying its workers.’

Reform may this result in increased competition between co-operatives and between co-operatives and other businesses if it can facilitate their growth through the economies of scale their utilise. Increased competition may itself then drive innovation, which in turn could lead to further, increased economic growth. Higher wages and lower prices could equally benefit the economy, as well as social well-being. All of which could also benefit the Treasury, and hence public services, through increased receipts from taxation. Simplification and modernisation of the law may thus have significant benefits.

- The second is a project that we intend to launch this year. Its focus is reform of the law concerning the agricultural sector in Wales. The law in this area is various. It is spread across various pieces of legislation. From the Board of Agriculture Act 1889, the Hill Farming Act 1946, various Agriculture Acts, to the more recent Agricultural Sector (Wales) Act 2014 and the Agriculture (Wales) Act 2023, there is plenty of scope for complexity. There is equally plenty of scope for provisions to no longer be fit for purpose for a modern, agricultural economy. Over 30 pieces of potentially relevant legislation might suggest that there is scope for anomalies to have grown. It ought to be evident that legislative complexity will increase economic burdens placed on the agricultural sector, both in terms of the need to obtain effective legal advice and in terms of compliance. The same can be said where the law is obsolete or creates anomalies.

- To improve matters, we intend to consider the potential for codification of the law. And in doing so we will consider how to simplify and modernise it. The first part of the project will be a scoping study, to identify the various laws that will fall within its scope. Depending on the view taken by both the Commission and the Welsh Government once that initial phase has been completed, we would anticipate the development of a new Agricultural Code. Such an approach, if pursued to its conclusion, will have as its clear intention – one we would very much hope to realise – to make the law clearer and more accessible. To make its future revision also more straightforward, as only one Act, the Code, will stand in need of revision; a point that will also assist the Commission in future as it will make systematic review, development and reform more efficient. And in doing so it will be readily evident what the consequences for other parts of the legislative framework are. Clear. Simple. Comprehensive. In this way we seek to improve the rule of law in this area and, in doing so, reduce the economic friction costs associated with legal compliance and thus provide an improved platform for economic growth.

- These are just two examples of how the realisation of the Law Commission’s statutory purpose can and does benefit society. They underscore the significant value that Lord Gardiner’s vision continues to have, and show that the benefit it has for the law and its development, goes beyond tidying up the statute book. That is why our purpose is and will continue to be guided by a commitment to improving the rule of law, and through that playing a significant role in the promotion of economic growth.

(4) Legal certainty and Transparency

- The next principles that guide our work are those of legal certainty and transparency; both of which Lord Bingham also identifies as inherent in a commitment to the rule of law. These principles have a dual role to play where the Commission is concerned.

- The first role can be illustrated by the Sentencing Code 2000, the development of which was spearheaded by Professor David Ormerod while he was a Law Commissioner. The Code provides guidance on the available sentences for criminal offences in England and Wales. It is a complete code. It consolidated over 50 pieces of previous legislation, simplifying and updating the law in this area. It also, again consistently with our objectives, removed anomalies and ambiguities in the law. But, it did more than that. It rendered the law transparent. It did so through increasing legal certainty. It did so in an area where both are of significant importance, not least where the rule of law is concerned, as criminal sentencing effects individual liberty as well as public safety, amongst other things.

- Lord Bingham illustrated the problem that can arise where there is a lack of transparency and certainty where the criminal law is concerned. In his book The Rule of Law he noted how in one case an individual was convicted and sentenced to serve a community service order. The trial judge was satisfied that he could properly make such an order, and that the individual had been properly convicted. On appeal, the Court of Appeal intended to uphold the conviction, and hence the sentence. Both the trial judge and the Court of Appeal relied on specific Regulations that were brought into force in 1992. As Lord Bingham went on to explain,

‘Neither the trial judge, nor the prosecutor, nor defending counsel, nor the judges of the Court of Appeal knew of [later regulations that replaced the 1992 Regulations], and they were not at fault.’

They were not at fault because at the time because there was no fully comprehensive database of legislation with, as you would expect today, hypertext links to connected, relevant legislation. The sheer mass of legislation in the area rendered it effectively impossible for lawyers and judges, never mind the public, to know the law, apply it and abide by it.

- While the state of sentencing law did not reach such levels, the position prior to the Sentencing Code was an instance of a difference in degree. Complexity created by so many pieces of legislation dealing with sentencing rendered the law less transparent and less certain than it ought to be in such an important area. The importance of the Sentencing Code’s introduction cannot, as a consequence, be underestimated. It is an approach to law reform that will continue to guide us as we approach our future projects.

- Legal certainty is focused on the substance of our work. The second aspect of transparency and certainty’s role concerns the process that we adopt. From its creation the Commission has engaged widely in the development of its proposals. It has always, for instance, consulted widely with a whole range of stakeholders. It has done so from its very first working party, which considered reform to freehold title. When its work and proposals in this area were first published, the first Commissioners ensured that they took active steps to engage with conveyancers. That profession had the practical knowledge of the area. They would be able to provide expert analysis of the proposals, and were thus very well placed to provide feedback on the Commission’s proposals. The Commission promoted this form of engagement by publishing its working party in the New Law Journal. It took a step at that time that would best ensure that its proposals reached its target audience.

- Ensuring transparency in this way at the most basic level is a way to secure the best quality and breadth of feedback on our proposals. It was and is a means to improve our working. It draws our attention to unforeseen adverse consequences, ambiguities and weakness. In that way it contributes to the quality of our proposals, to the practicality, and their utility. Thus it is an essential means through which our processes can help our proposals to promote legal certainty, as much as they can give effect to our other guiding principles. We make considerable efforts to ensure that we are able to engage widely with interested parties and the public where each of our projects are concerned to further these principles. I encourage everyone – and I mean everyone – to participate in our consultations, which are entirely public, published on our website, and we welcome contributions and feedback from members of the public, whether legally qualified or not.

- There is a deeper reason why our processes must engage with the public. Law reform is an important part of our democratic process. It is as much a democratic activity as the process through which proposed legislation is considered by the Government and then by Parliament. Our contribution arises at an early stage of the process. Because of that though we need to ensure that we fully engage with the public so that they, you, we are, and can be seen to be, a part of the process. To help shape the development of our proposals and in that way feed the public’s views to Government and Parliament via our engagement. That being said, we will need to consider how we can best engage the public in the future. Formal consultation documents, articles in the New Law Journal, and other traditional means of engagement may no longer be sufficient to fully engage with all those who may wish to contribute their views, their experience and expertise. We may need to make greater use of social media. A Law Commission podcast series, for instance, may bring our work closer to the public. Equally, might we collaborate with other civic society organisations, with universities.

- However this consultation is done, it is fundamentally important that we take steps to ensure that we maintain our relationships with Government, Parliament, the Judiciary, and the legal profession, a commitment to transparency requires us to take proper steps to maintain and broaden our engagement with the public. Our work should have a positive and constructive relationship with all our audiences if we are to continue to improve the quality of the law. Just as we are required to modernise the law, we must ensure that we modernise the way in which we approach that task.

(5) From Individual wellbeing, protecting the vulnerable to innovation and value for money

- I turn now to the final three principles. These focus on ensuring: first, that the law promotes individual well-being, while protecting the vulnerable; secondly, that it delivers innovation and cutting-edge opportunities; and, finally, that it delivers value for money. I can only touch on them, and there is less black letter law to be said about them, but that should not be taken to suggest that they are less important that the other principles.

- I stressed earlier how important legislation was for promoting economic growth and the rule of law. The former might be taken as suggesting that the Law Commission should be guided by a neo-utilitarian approach. That it should consider its proposals by reference to a strict economic cost-benefit analysis. Such issues are, of course, relevant. But there is more to law reform, and to the rule of law, than that, and we are not guided by economic imperatives. Laws must respect individual dignity, and promote individual rights and responsibilities. They must provide a just framework for social as well as economic development. They must be just for all, because everyone is equal before the law. Hence they must protect the vulnerable. Projects such as those we are considering on kinship care are thus just as important as those which focus specifically on legal and societal innovation, such as our proposed project on digital assets in private international law. As a single example, we are currently considering the law on burials and disposal of the dead. That is not being done for economic reasons, although there will be economic implications. Re-use of burial plots or grounds in an increasingly crowded society is a thorny subject with which we must grapple. Lots of people will have a range of different views, and many of those views will be influenced by their personal experiences, not which proposal will have the greater economic benefit.

- It is increasingly likely, as the first quarter of the 21st century has shown, that the Commission will have an increasing focus on modernisation in the light of digital developments, and particularly those concerning the use and prevention of the abuse of artificial intelligence. We have already started to do so, where our work on automated vehicles (work carried out collaboratively with the Scottish Law Commission) resulted in the Automated Vehicles Act 2024 and our work on digital assets resulted in the introduction of the Property (Digital Assets etc) Bill 2024. Our work in this and related areas is only just beginning.

- As we approach this work, we will – as we do generally – approach it so as to promote rather than stifle innovation and do so in ways that deliver value for money for society. In that latter respect, given the evident benefits to the economy, individual and social development, and the rule of law that the Law Commission over the last sixty years has contributed and, more than that, enhanced through its work, I very much hope the case for it delivering value for money is more than made out. We do not cost very much money – our budget it tiny. We have fewer than 70 members of staff, both full and part time. We occupy but a tiny part of one floor in the offices at 102 Petty France. But we deliver benefits far out of proportion to our cost – Electronic Trade Documents Act is calculated to bring economic benefits measured in the billions of pounds over the next few years, as a direct result of a bill attached to a report that cost a couple of hundred thousand pounds.

- With these points in mind, I want to end today’s lecture by recalling something my ultimate predecessor Lord Scarman said in a lecture when the Commission was in its infancy. He said this, ‘. . . I would say to you who are the lawyers of the future, that in about 10 or 15 years’ time take a look at the Law Commission. Has it become just another department of state? If so, get rid of it, but if it hasn’t, continue to give it your support.’

- I would pose the same question to you – the lawyers of the future. Who knows, we could well have a future Chair of the Law Commission or future President of the Supreme Court sitting here this evening, or present at the lecture I gave at Trinity St David’s law school yesterday afternoon.

- Lord Scarman finished his lecture on that point, posing a question for the lawyers of the future. He did not speculate on what the answer might have been for those lawyers of the future, although we can reasonably conclude that he would have hoped, or anticipated, a positive response. I think we can be more confident. We certainly are not just another department of state. I would very much hope and expect that you will be able to continue to support the Law Commission; that with a fifth Commissioner and through being guided by our six principles over the next forty years, never mind the next ten or fifteen, it will continue to play a valuable, an essential role in the maintenance and development of the laws of England and Wales.

Thank you all very much.

References

[1] L. Scarman, The Law Commission – Its Aims and Achievements, (1974) City of London L Rev 7.

[2] W. Holdsworth, The Movement for Reforms in the Law, (1793-1832), (1940) 56(1) LQR 33.

[3] R. J. Sutton, The English Law Commission: A New Philosophy of Law Reform, 20 Vand. L. Rev. 1009 (October 1967).

[4] N. Marsh, Lord Gardiner, (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography) (OUP, 2004).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Lord Reid, H.L. Deb. Vol. 271 (9 December 1965) col. 437 cited in F. Bennion, Law Commission – QMC Colloquium – Law Reform: Can We Do Better? (1986), which is available here: https://web.archive.org/web/20060421180612/http://www.francisbennion.com/pdfs/fb/1988/1988-002-zellick.pdf.

[7] L. Scarman, ibid.

[8] L. Scarman, ibid.

[9] Law Commission, Annual Report 2023-2024, at 24, which is available here: https://cdn.websitebuilder.service.justice.gov.uk/uploads/sites/30/2015/05/25.11_LC_AnnualReport_23-24_WEB.pdf. A complete list is available here: https://lawcom.gov.uk/our-work/implementation/table/.

[10] See, Justice (Northern Ireland) Act 2002, ss.50 to 52 and the website of the Law Commission of Northern Ireland, which is available here: https://www.nilawcommission.gov.uk/about-us.htm.

[11] The three reports are available here: https://lawcom.gov.uk/project/renting-homes/. The 2006 report was rejected for England, while accepted in principle for Wales, a clear instance of divergence in action.

[12] CPR Pt 56, PD 56 and PD56A, the latter applying to Wales.

[13] Law Commission, Form and Accessibility of the Law Applicable in Wales, (2016, Law Com No 366) (the 2016 Report), which is available here: https://cdn.websitebuilder.service.justice.gov.uk/uploads/sites/30/2016/10/lc366_form_accessibility_wales_English.pdf.

[14] 2016 Report at 28.

[15] The Civil Procedure Act 1997 (Amendment) Order 2017 (SI 2017/1148).

[16] Lord Etherton MR, Laws, Procedure and Language; Civil Justice and Cymru, (2019, Legal Wales) at [16], which is available here: https://www.bailii.org/uk/other/speeches/2019/H4QY5.pdf.

[17] Lord Etherton MR (2019) at [21].

[18] Law Commission, Form and Accessibility of the Law Applicable in Wales – Consultation, (2015, Law Com CP 223) at 3.

[19] E.g., Lord Thomas, CJ, Developing commercial law through the courts: rebalancing the relationship between the courts and arbitration, (2016), which is available here: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/lcj-speech-bailli-lecture-20160309.pdf; Lord Burnett CJ, The Hidden Value of The Rule of Law And English Law, (2022), which is available here: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Blackstone-Lecture-2022-final2-1.pdf; Lady Carr CJ, Mediation after the Singapore Convention, (2025); Lord Hermer A-G, Speech to the Standing International Forum of Commercial Courts, (15 January 2025), which is available here: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/attorney-generals-speech-to-standing-international-forum-of-commercial-courts.

[20] Lord Burnett CJ (2022) at [20].

[21] Lord Bingham, The Rule of Law, (Penguin, 2010), Chap. 3.

[22] Law Commission, Review of the Co-operative and Community Benefit

Societies Act 2014 – Consultation Paper (Law Comm. CP 264), which is available here: https://cdn.websitebuilder.service.justice.gov.uk/uploads/sites/30/2024/09/Co-ops-consultation-final-1.pdf.

[23] For a summary of the main pieces of relevant legislation, see https://law.gov.wales/key-legislation-agriculture-and-horticulture.

[24] See Terms of Reference for the project, which are available here: https://cdn.websitebuilder.service.justice.gov.uk/uploads/sites/30/2024/04/Agricultural-law-in-Wales-terms-of-reference.pdf.

[25] Lord Bingham, Ibid.

[26] Professor David Ormerod KC, Sentencing Code – 10 things you need to know, (2020), which is available here: https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/The-Sentencing-Code-10-things-to-know-revised-1.pdf.

[27] Lord Bingham, ibid at 41-42.

[28] P. Mitchell, Strategies for the Early Law Commission, in J. Lee, M. Dyson & S. Wilson Stark (eds.), Fifty Years of the Law Commissions: The Dynamics of Law Reform, (2016, Hart).

[29] Which is available here: https://lawcom.gov.uk/project/kinship-care/.

[30] Which is available here: https://lawcom.gov.uk/project/digital-assets-and-etds-in-private-international-law-which-court-which-law/.

[31] Lord Scarman, ibid.